By Cipperly Good, the Richard Saltonstall Jr. Curator of Maritime History

The sea chantey is the moment’s hottest fad on TikTok, a social media platform dedicated to song and dance. The chantey is meant to be bellowed six feet apart and to bring disparate work crews from many different nationalities, ethnicities, and socio-economic backgrounds into alignment to “pull together” towards a common purpose. In the nineteenth century, it got sailing, fishing, and railroad crews to act as a unified force of effort. Today, the chantey allows us to raucously sing together in call and response, albeit remotely, into the isolation caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, a tense presidential transfer of power, a racial reckoning, and seasonal affective disorder.

Although sea chanteys are an oral tradition that allowed the chanteyman to adapt the words to include inside jokes only the crew understood and pointed references to the bully mate or captain in coded language, some intrepid collectors copied down their favorite versions. Luckily for us at Penobscot Marine Museum (PMM), our very own Joanna Carver Colcord (1882-1960), a Searsport Sea Captain’s daughter and founding member of PMM, was one such compiler. In her foreword to Roll and Go: Songs of American Sailormen, written in 1924, she writes:

The following examples of these work-songs of the sea are drawn in part from my own memories of years spent on blue water under sail from 1890 to 1899, mostly on voyages between New York and various ports in the China Sea. In part, they are songs learned from my father, who loved them and sang them well, and whose seagoing began about the year 1874. This makes my versions of the songs later than the “classical” period of shanty-singing, which extended from about 1840 to the time of the Civil War. I also owe grateful acknowledgement to many shanty-singers still alive…

Shanties naturally fall into three main divisions on a scale of occupational classification: short-drag shanties [i.e. hauling sail onto top of yard], halyard shanties [i.e. raising sail], and windlass or capstan shanties [i.e.hauling up anchor]. The form of the shanty for each of these three divisions is quite different, since it is fitted to an altogether different job aboard ship. I have used this natural classification in the following pages as a means of dividing the collection into readable lengths, and also as an aid to the general reader in forming a clear conception of what the shanty stood for and how it was used.

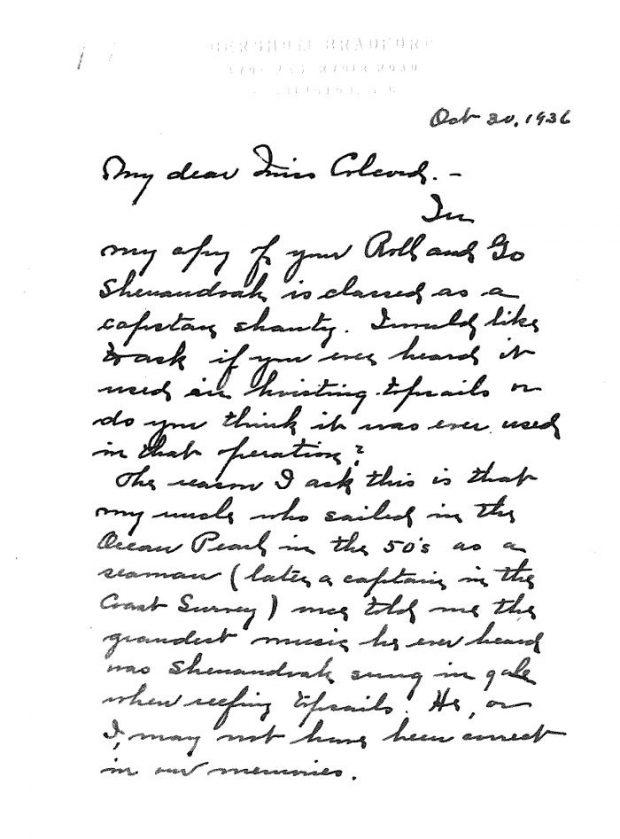

Of course, when setting out to be the expert on a topic, there is always push back. Colcord lays out two pages of debate on the spelling of shanty versus chantey in her foreword. In our collection, we have correspondence between Colcord and Gershom Bradford on whether the song “Shenandoah” could be a halyard or capstan shanty:

PMM 29-1062, Colcord Collection

October 30, 1936

My dear Miss Colcord,

In my copy of your Roll and Go, Shenandoah is classed as a capstan shanty. I would like to ask if you ever heard it used in hoisting topsails or do you think it was ever used in that operation?

The reason I ask this is that my uncle who sailed in the Ocean Pearl in the 50’s as a seaman (later a captain in the Coast Survey) once told me the grandest music he ever heard was Shenandoah sung in gale when reefing topsails. He, or I, may not have been correct in our memories.

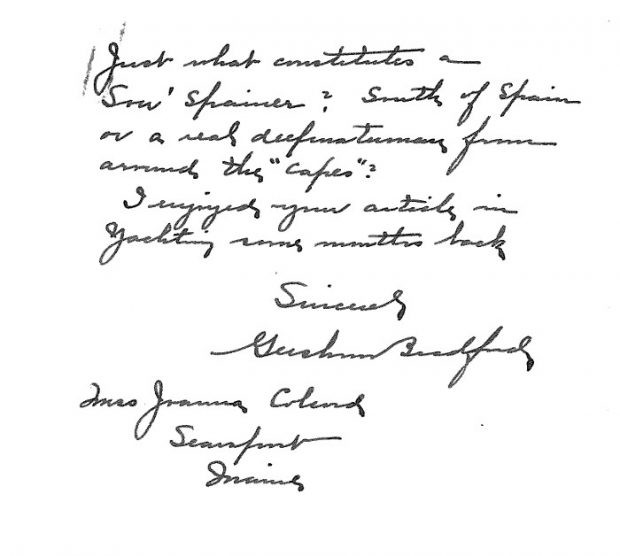

Just what constitutes a Sou’ Spainer? South of Spain or a real deepwaterman from around the “Capes”?I enjoyed your article in Yachting some months back.

Sincerely,

Gershom Bradford

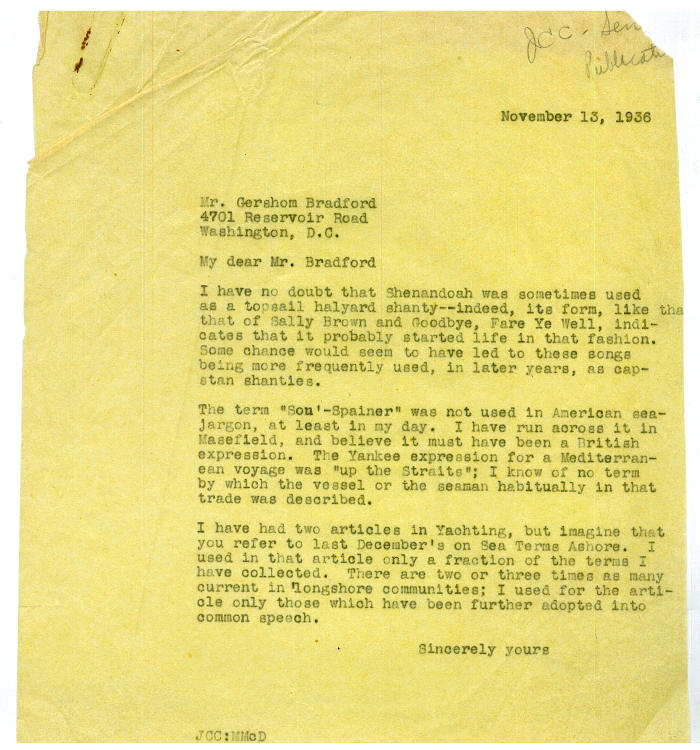

PMM 29-1062, Colcord Collection

November 13, 1936

My dear Mr. Bradford

I have no doubt that Shenandoah was sometimes used as a topsail halyard shanty—indeed, its form, like that of Sally Brown and Goodbye, Fare Ye Well, indicates that it probably started life in that fashion. Some chance would seem to have led these songs being more frequently used, in later years, as capstan shanties.

The term ”Sou’Spainer” was not used in American sea-jargon, at least in my day. I have run across it in Masefield, and believe it must have been a British expression. the Yankee expression for a Mediterranean voyage was ”up the Straits”; I knew of no term by which the vessel or the seaman habitually in that trade was described….

Sincerely yours

Gershom Bradford III (1879-1978), who wrote the letter of inquiry to Joanna Colcord, was no stranger to the sea. He trained at the forerunner of the Massachusetts Maritime Academy to be a merchant marine captain, served as a bridge officer for the East Coast steamers used by the US Coast and Geodetic Survey, rose to the rank of lieutenant as a navigator in the Navy Hydrographic Office, and trained the next generation of navigators at the US Shipping Board School in Boston. Bradford was in charge of writing the Notice to Mariners, put out by the Naval Hydrographic Office to correct errors or changes on nautical charts. In his private time, Bradford published books and articles on sailing and navigation, and like Joanna, wrote about sea terms. His book was titled: The Mariner’s Dictionary: A Glossary of Sea Terms, whereas Joanna’s was Sea Language Comes Ashore. Both also published articles in The American Neptune.

His uncle, and namesake, Gershom Bradford II (1838-1918), as noted in the letter, served as a seaman on the OCEAN PEARL in the 1850s, and later as a nautical surveyor and captain in the US Coast Survey. The US Coast Survey, which was renamed the Coast and Geodetic Survey in 1878, and finally became part of NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) in 1970, surveyed and created maps for mariners. Bradford’s name shows up as the Hydrographic Inspector on nautical charts. At the time of his 1871 marriage in San Francisco to fellow Duxbury, Massachusetts native Minnie Winsor, Bradford was an assistant on the US Coast Survey schooner MARCY surveying the shoals and coastlines of the United States. Minnie joined him on the surveys aboard the MARCY and later the YUKON and PALINURUS. While government ships are not known for their sea chanteys, Bradford definitely used the work songs in his time in the merchant marine. The OCEAN PEARL mentioned in the letter could possibly be the ship built in Charlestown, Massachusetts by T. McGowan in 1853.