Martin R. Bartlett Collection

Marty Bartlett, now in his eighties, is done with the ocean, but he’s a character who was clearly shaped by his lifelong interaction with it. His photographs are a privileged on-deck view of tuna and sword fishing during a critical time for those fisheries. While searching for images from PMM’s National Fisherman Collection for a book he was writing (Wind Shift at Peaked Hills, a creative nonfiction account of sword fishing) , he offered to donate his work here. While the images don’t tell a Penobscot Bay story, their powerful place in the recent history of the Gulf of Maine made the choice of accepting his gift an obvious one.

Bartlett grew up fishing with his dad along the shores of Cape Cod. The pair missed a couple of years during the second World War; he recalls seeing columns of black smoke from burning tankers offshore. After the war, fish stocks rebounded somewhat; he could catch pollock with a mackerel jig off the beaches. The father-son ritual was finally abandoned after dad, in a lapse of attention, backed the Model A into the garage with the fishing rods standing like flagpoles, snapping all of them.

Bartlett enlisted in the Coast Guard for four years after high school. This intensive sea time gave him the chops to find work at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, where he spent six years crewing on research vessels; there, he worked his way up to second mate. During this stint, he was lured into the WHOI game fish tagging program by its progenitor, research associate Frank Mather. Mather had achieved some renown for his project, which involved a novel tagging mechanism for large pelagic fish; his tags used a small barb which was embedded in the thick skin of a tuna or swordfish from the end of a long pole. In contrast to loop and other tag styles, these remained in place for four years or more. Tags, of course, allow scientists to track the growth and migratory patterns of fish, which in turn can provide insight into the impacts of fishing on the vigor of populations.

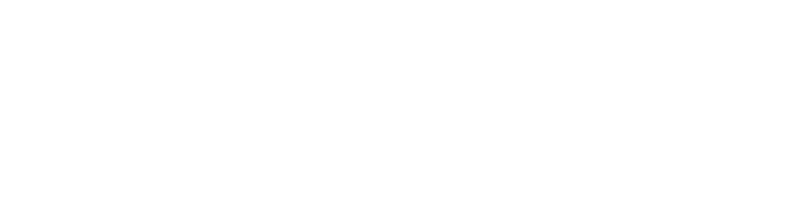

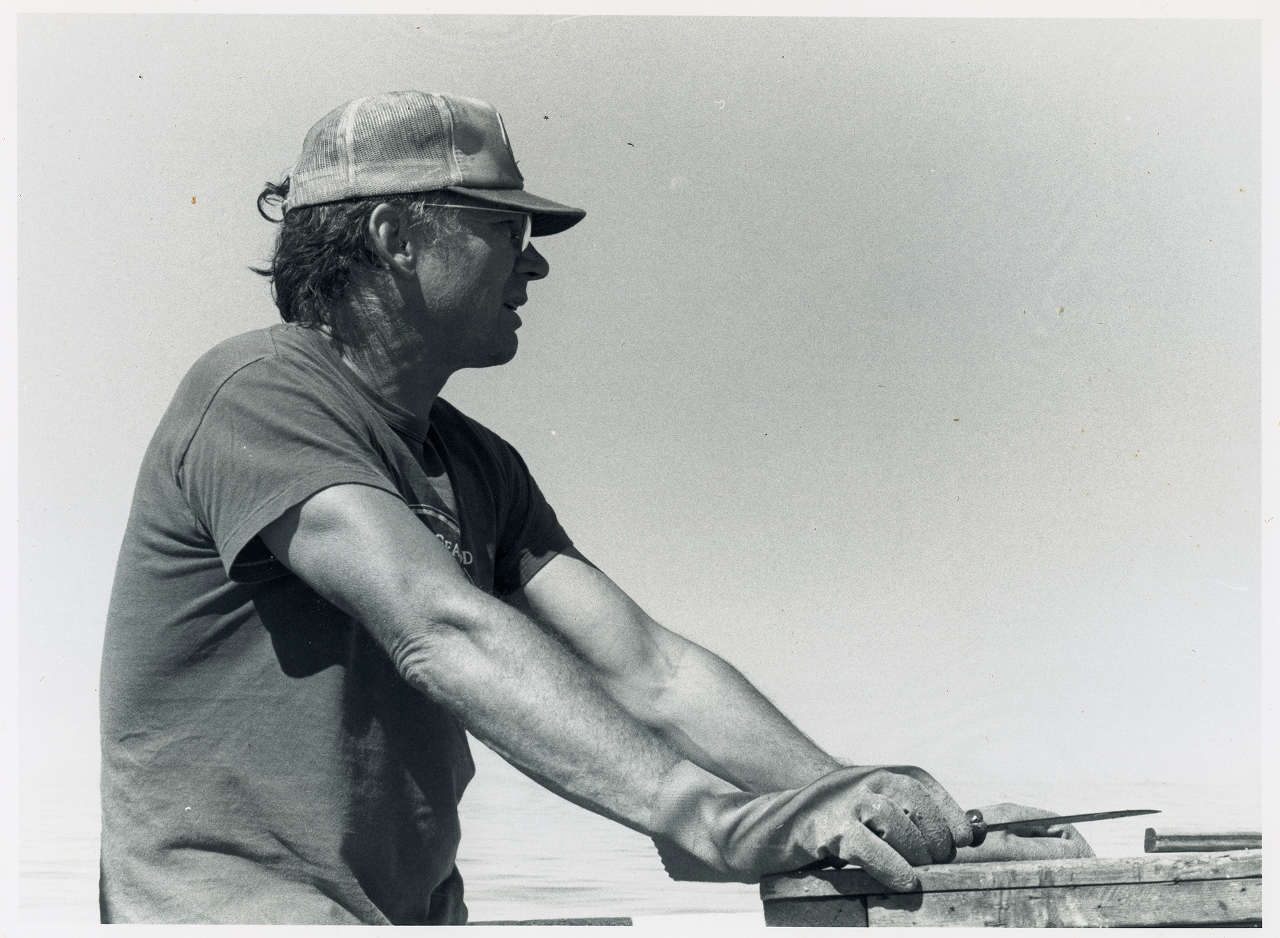

Marty Bartlett in action.

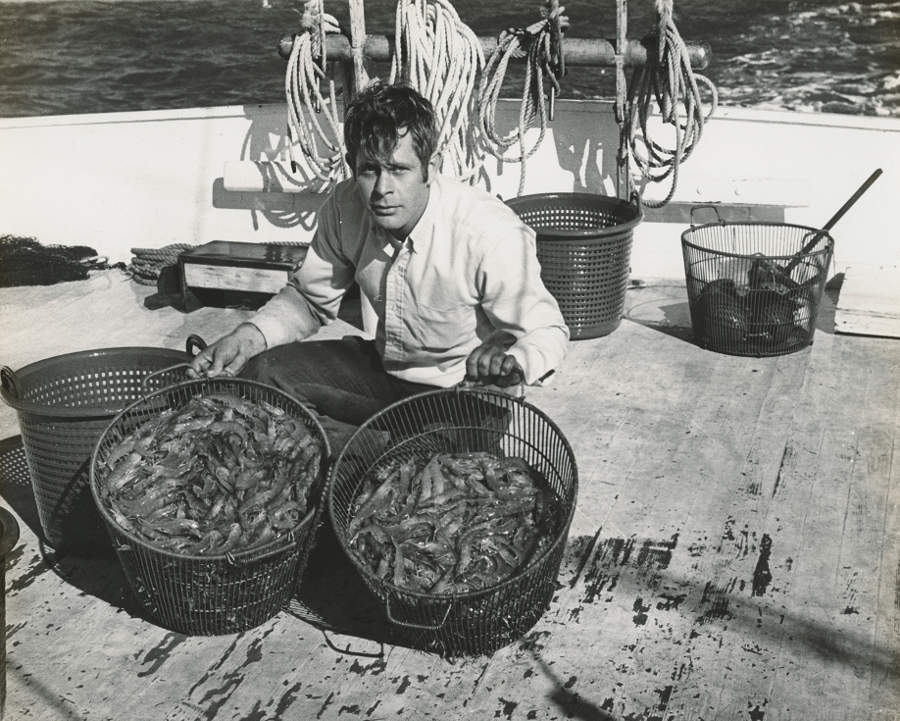

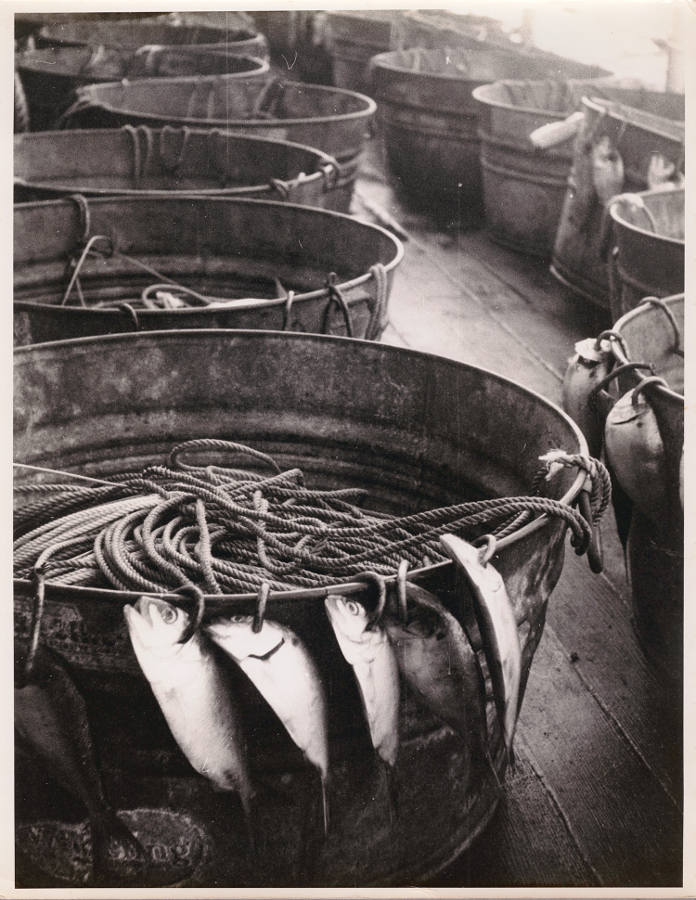

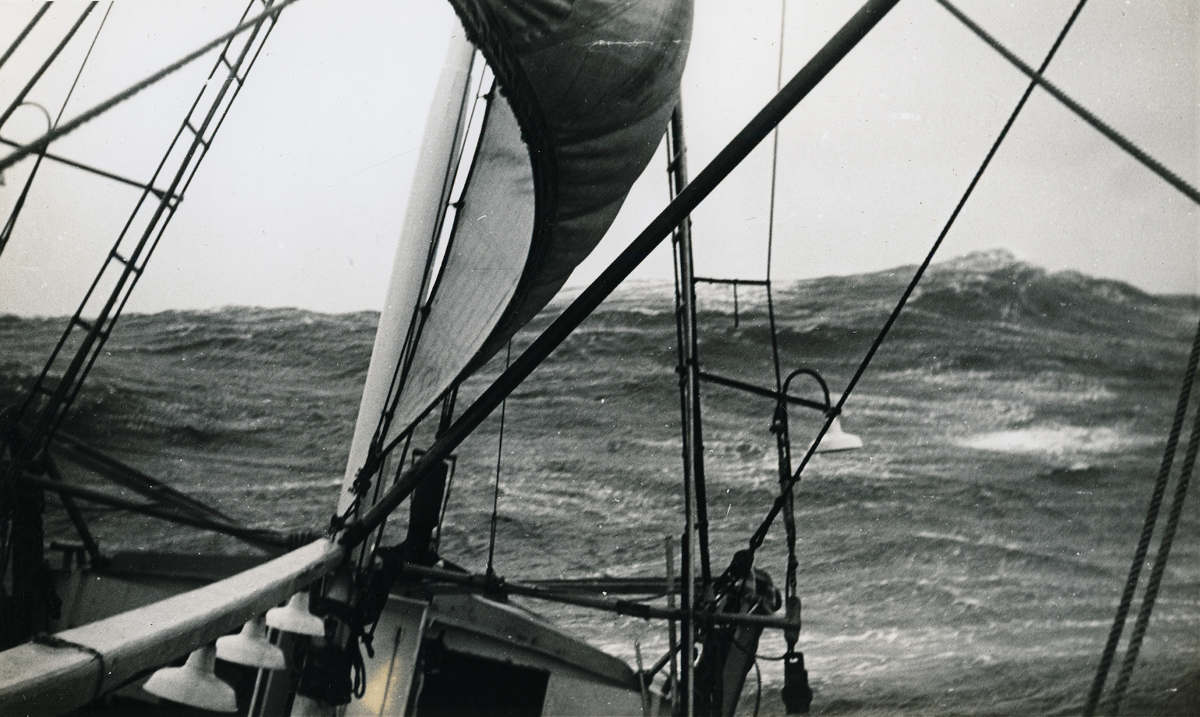

He’d bought a Leica and was shooting some 35mm film showing the work he was a part of, but boat crew and research personnel don’t often have the luxury of being observers, or “tourists”. It wasn’t until a few years later, when he started getting invitations to act as a guest artist on commercial fishing vessels, that his moment came to document the dynamic realities of harvesting large predator fish. These captains were of course in pursuit of profitable landings, but research entities like WHOI were willing to pay them to tag some animals and throw them back. Bartlett captured scenes of both longlining and seining; US fishermen in the North Atlantic were late adopters of these practices, both of which had a devastating impact on swordfish and tuna stocks.

Bartlett’ career had further significant chapters; he eventually bought his own boat, the Penobscot Gulf, a burly steel-hulled workhorse which had been used to haul fuel to the islands of Penobscot Bay during WWII. He fished commercially from the Gulf with a crew for several years until swordfish, tuna, and groundfish stocks began to disappear in the 1980s.